Susan Cooper (1935-)

http://www.thelostland.com/A selection of her works which have historical aspects:

The Dark is Rising sequence is based on Arthurian legend and Celtic and Norse myth: Over Sea, Under Stone (1965), The Dark Is Rising (1973), Greenwitch (1974), The Grey King (1975), Silver on the Tree (1977)

Seaward (1983, new edition coming in 2013) draws on Celtic myths

The Boggart (1993) and sequel The Boggart and the Monster (1997) feature ghosts, people and places haunted by the past

King of Shadows (1999) time-slip (present day and Shakespearean London), adapted for stage (2005)

Victory (2006, new edition coming in 2013) two times (Battle of Trafalgar, 1805, and present day) and two protagonists who are connected by a scrap of cloth in a book.

Interviews with Susan Cooper

| What was your childhood like? | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| What are your ties to Wales? | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| When did you first start writing? | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| What led you to Oxford? | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Is it true that Tolkien was one of your professors? | ||||||||||||||

| J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were both teaching when I was at Oxford and without a doubt influenced the lives of all of their students. As dons, they had set the rule that the Oxford English syllabus stop at 1832 and that it be heavy on Middle English and writers like Malory and Spenser, so, as a friend of mine says, they taught us to believe in dragons. They were both often to be seen drinking beer in a pub called the Eagle and Child, known as the Bird and Baby. I never personally met Tolkien or Lewis, and I’d never heard of Narnia, but we were all waiting eagerly for the third volume of The Lord of the Rings to come out, and I loved going to Lewis’s booming lectures on Renaissance literature. Tolkien lectured on Beowulf and was rather mumbly, except when declaiming the first lines of the poem in Anglo-Saxon, beginning with a great shout of “Hwaet!” | ||||||||||||||

| Did you start writing books right away? | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| How did you manage being a journalist and a fantasist at the same time? | ||||||||||||||

Next I wrote a book about the war, Dawn of Fear, which is totally autobiographical except that I turned myself into a boy, and for nine years I wrote a weekly column called “Susan Cooper In America” for a Welsh newspaper. I also wrote a biography of the English author J.B. Priestley. For me, combining journalism and fiction in my writing life worked quite well. | ||||||||||||||

| Why would someone so British move to the United States? | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| How did you come to write the Dark is Rising sequence? | ||||||||||||||

The homesickness influenced my writing, certainly. Life improved after my son Jonathan was born in 1966, and my daughter Kate 18 months later. I learned to drive, to ski, to cook enormous meals for teenagers and graduate students, and tried (rather less successfully) to understand American football. I returned regularly to England for visits. But my homesickness never went away.

On another piece of paper I wrote the very last half-page of the entire story, and then I spent the next six years writing the rest of the sequence—and pulled out that half-page when I reached the end of Silver on the Tree. | ||||||||||||||

| Did your source of inspiration change after you wrote The Dark is Rising? | ||||||||||||||

| After the five Dark Is Rising books, when everyone expected something similar, I wrote a very different fantasy called Seaward. It was written during an awful year when my marriage broke up and both my parents died, but it has hope in it all the same—and one character who still haunts me, a strange little creature named Peth. My book ideas since have all been very different from each other, and gradually I turned my storytelling towards theatre and film as well. | ||||||||||||||

| Did you always write for the theatre as well? | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| What did you write with Hume Cronyn? | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Have you worked on other collaborations? | ||||||||||||||

| Every book is a collaboration between author, editor and illustrator. My editor, the late legendary Margaret K. McElderry, paired me with wonderful artists—notably Ashley Bryan and Warwick Hutton for some of my picturebooks, and Michael Heslop and Trina Schart Hyman for jacket art. Also I’ve worked on musical collaborations with composers, which has been great fun, and on multi-author anthologies. The latest project with the NCBLA, “The Exquisite Corpse Adventure,” was actually a collaborative game, which I encourage young writers to try for themselves. | ||||||||||||||

| How did your other fantasy novels come about? | ||||||||||||||

At the same time that I was working on screenplays, I wrote picture books—retellings of folktales from the British Isles full of myth and magic: The Silver Cow, The Selkie Girl, and Tam Lin. For a long time I wanted to write a story about the invisible mischief-making spirit known in Britain as a boggart, and suddenly when I was on vacation in Scotland with a friend we saw a castle where I instantly knew my boggart lived! So out of that came two cheerful fantasy novels in the 1990s: The Boggart and The Boggart and the Monster. Eventually the theatre and the writing sides of my life came together in my head, and I found I wanted to write a story about a modern American boy actor who finds himself onstage with William Shakespeare at the Globe Theatre, in London. At first I pushed this idea away, since I knew it would mean lengthy research into 17th century English life, not to mention Shakespeare, but I had made the mistake of mentioning it to Jack Langstaff, who proceeded to remind me of it enthusiastically at monthly intervals for a year. So I finally wrote King of Shadows, and sent the very first copy to Jack.

Having written a timeslip book that gave me the chance to meet my greatest hero, Shakespeare, I thought again about a tiny long-ago incident that had been floating about my head for years. Another hero, if you’re English, is Admiral Lord Nelson, who was killed at the Battle of Trafalgar while helping to save his country from being conquered by France and Spain, and somewhere I had read that the crew of his flagship H.M.S. Victory carried its tattered flag in his funeral procession through the streets of London. As his coffin was lowered into the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, the sailors were supposed to fold the flag to go down too— but they couldn’t bear it, because the flag was all they had left of him. So they ripped it apart, and each one of them kept a piece. I thought: suppose one of those sailors was a ship’s boy, and suppose he kept his piece of flag all his life—and suppose it comes down to the present, to another boy—no, to a girl—and suppose— So I wrote Victory, about 18th century Sam and 21st century Molly, and it gave me the chance to meet Nelson. As for what’s next.... Readers often ask writers where their ideas come from, incredulously, as if they already know it must be from an elusive and mysterious source. You can read my essays in Dreams & Wishes for my thoughts on imagination, and creating story. | ||||||||||||||

| Where do you currently live and work? | ||||||||||||||

On the window sill there’s a magic talisman, a round green glass float once attached to a fisherman’s net, that I rescued from the beach. Not a beach here in America, but beyond the horizon—in Wales. |

Susan Cooper talks to Nikki Gamble for the Just Imagine Story Centre

I’m particularly delighted to have the opportunity for this interview with you, because The Dark is Rising was one of the formative books from my childhood. It ranks with Alan Garner’s The Owl Service as an all time favourite. It is remarkable how so much classic fantasy writing was born in Oxford starting with Lewis Carroll and continuing through to Tolkien, Lewis, Garner, you and now Philip Pullman. You were taught by Tolkien, weren’t you?

Well, in theory Tolkien and Lewis taught us. I was reading English and Tolkien was lecturing on Anglo-Saxon literature. He used to begin his first lecture with the first few lines of Beowulf delivered with great panache in Anglo-Saxon. Lewis lectured on Renaissance literature. But of course the examination schools in Oxford are huge and I was part of an enormous audience. That was my only exposure, as the Americans say, to these two Fellows.

ill Paton Walsh has a theory about the reason Oxford has given rise to this flourishing of fantasy literature is because the syllabus stopped at 1832. I think Tolkien and Lewis were responsible for that, because they believed that you should have a great grounding in early literature. They taught us all to believe in dragons.

Alan Garner was there but I think he read the Classics. The first time I met him we were at a conference in Aberystwyth. We talked and talked and talked. It was like meeting a brother. And he asked me, “When were you at Oxford?” And I said, “1953 to 1956,” and he said, “I knew we’d been in the same room together somewhere.”

There was a flowering of mythic children’s literature in the post war period. What do you think it was about that time that made it such fertile ground?

I think it must have been lots of things coming together. As far as I can gather, children’s lists really only grew just after World War Two. My American editor, who is now in her 90s, was one of the first children’s editors in the States. I think also the fact that those of us who were reading English at Oxford were firmly rooted in Beowulf and Spenser.

If we follow the trajectory of fantasy writing, it moves from the alternative worlds created by Tolkien and Lewis through to what has been termed ‘low’ or ‘urban’ fantasy, where the magic exists in the primary world. That’s the case with The Dark is Rising and The Owl Service. Alan Garner once wrote that if you find a mandrake in El Dorado then you won’t be surprised but if you find one roaming the Cheshire countryside then that is something altogether more frightening (more eloquently expressed but words to that effect). The image from The Dark is Rising, that stays with me is Will Stanton in the Buckinghamshire countryside, it is winter, and the ploughed fields are covered with snow; you can almost hear the rooks in the rookery. It’s that evocation of atmosphere, a real feeling for place in your work, and in Garner’s, that is so beautifully realised and utterly compelling.

Place is usually important. Also there is the fact that I was a small child in World War Two, so bombs and the air raid shelters were very much part of my personal landscape, which gives a very strong sense, not just of us and them, the good and the bad, and the dark and the light, but also a sense of constant menace. And I guess that is absorbed by the imagination. If you happen to have a talent for writing, then it’s going to come out at some point.

Your sequence is titled The Dark is Rising which emphasises the presence of menace that you have talked about.

Yes, when the sky is full of bomber, you’re hauled down into the air raid shelter, and you can feel and hear the bombs getting closer and closer, there’s one candle, and the flame is shaking with each bomb that comes down – well that menace is real.

My war book was called Dawn of Fear which I wrote in the late 60s I think. It was autobiographical, about being a child in World War Two, except that I changed myself into a boy. The effect of being a child of the War goes down so deep that you can’t get rid of it. I’m just thinking, goodness knows what it does to the children of Iraq at the moment.

In later writing, the Boggart books, the tone is very different. There’s a solemnity to The Dark is Rising, that isn’t there in the later books.

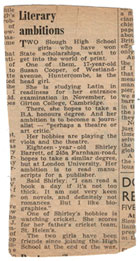

Yes. I never really thought about what I was doing but there is a division between the first books and the others. You were a journalist, so how did you move into writing books for children? When I was a reporter on the Sunday Times we had a page called 'Mainly for Children', which the Art Editor had set up, and some of us did things for it just for fun.

One day the Literary Editor came into my office one day with a piece of paper and said, “You should have a go at this.” It was a competition set up by Amis Benn, the publishers of E Nesbit, for a family adventure story. They were offering £1,000 which was more than I was earning. That was a fortune. It was huge. I started to write what I thought was a family adventure story, and by the end of, the second chapter, there appeared a character called Merriman. My story metamorphosed into a fantasy, so it no longer qualified for the competition. I didn’t care, because I was absorbed by then. The story became Over Sea Under Stone. I left that first book open-ended because I liked the people in it, and I didn’t want to say goodbye to them, though I wasn’t considering writing a sequel.

And then my newspaper sent me to America. I met and married an American and went to live in the States. He was 20 years older than me, and had three teenagers. I was 28, and I was very homesick, which made me do a lot of reading about the history and prehistory, of England and Wales.

Ten years after writing Over Sea, I was cross country skiing in deep snow in a wood near where we lived in Massachusetts and I suddenly thought, I’m going to write a book about a boy who wakes up on his 11th birthday, and finds he can work magic. It’s going to be set in snow, just like this, but in England. I had seen a winter like that just once, when I was 12 in 1947. I started to make notes but it just sounded facetious so I pushed the idea into a drawer.

Some time later I reread Over Sea Under Stone, I don’t’ know why because it’s unusual for me to reread my books once they have been published. Then one very peculiar day up in the little study I had at the top of the house, I had the idea that would connect the books. I knew that there would be five books and in the course of the next few days I wrote down five titles, places they were going to be set and times of the year (which was very important). And I wrote down the last half page of the very last book, put it away. I actually used it when I got to the end.

Then I spent the next six or seven years writing those four books. It was wonderful. I was very envious of Philip Pullman when he wrote his trilogy, and of J K Rowling when she write her Potter books, because, to know that you have this lovely stretch of life ahead when you know exactly what you are going to be doing in the company of your characters is very comforting.

The sequence is set in Cornwall, Wales and in Buckinghamshire. We expect Wales and Cornwall to be steeped in myth but not so much Buckinghamshire… that’s more of a surprise.

It is now, but, you know, we’re talking about the Buckinghamshire of 60 years ago. When I was a kid we lived, down a little road off the Bath road about halfway between Slough and Maidenhead. There was a long road called Huntingdon Lane, North and South, a country road which went across at right angles and there were farms all around. From my bedroom window I could see Windsor Castle on the horizon, and there was an Iron Age fort not too far away. Within living memory a farmer had been ploughing and found a Roman mosaic pavement underneath one of his fields. It was things like that that gave a sense of history.

The little church St James the Less that’s in The Dark is Rising is still there in the village of Dorney. Fifteen years ago, the last time I went back, the little wood and the rookery were also still there near the church, and so was the vicar’s house which is the model for the house where Will and his family lived. In those days it was full of echoes, and I was a fairly solitary, child, so maybe I listened more carefully than most to the echoes. It was a lovely place to grow up with a sense of the past all around.

We would go on holidays to the Welsh village that my mother’s mother came from, and because my father worked for the Great Western Railway we would get something they called privilege tickets, which must’ve been cheap tickets, to go to Cornwall for summer holidays. So those places lodged in my imagination.

And did you ever see anything like a Greenwitch ceremony in Cornwall?

No [laughs]. It’s funny, every now and again, I get a letter from a scholarly academic wanting information about the derivation of the Greenwitch. I have to disillusion them and I say, “I made it up.” But, of course, there are ancient country rituals for invoking good luck in the harvest or good luck with fishing and so on.

Do you think the sense of place comes through so strongly in your writing because you weren’t living in Britain at the time? Was it partly nostalgia?

Oh hugely, yes.

Can we talk a little bit about the film?

They screened it for me a week before it was released in America, and I took my son and my daughter as moral support, and by the end of the film, Jonathan, to whom the book is dedicated, was sitting there in stunned silence. Kate and I were shouting at the screen. You’ve written screenplays but you clearly didn’t have a hand in this one. I have written for the screen, but a long time ago.

What do you think about the interpretation of the book? It seems to me that they just didn’t ‘get it’.

Selling the film rights to a book to anybody is a gamble, because you lose artistic control. There have been a huge number of film offers over the years. Just twice I have trusted people enough to give them an option on the rights. On neither occasion did the plans come to anything. I even wrote the screenplay for one.

This was the third time that I trusted somebody, and, what can I say? I was horribly disappointed. From the moment I read the script, I sent a long list of things begging them to make changes but it didn’t have any effect.

You are right, they didn’t ‘get it’. The film is not about the same things that book is about. The boy’s an adolescent, instead of the crucial age just before puberty, when you’re trying to find out who you are. It’s a very particular time, because once you’re into puberty you become so confused about your sexual identity. If you’re a girl, you’re looking at boys, and if you’re a boy you’re looking at girls. That’s what concerns the boy in the film. Plus, I’m haunted by the matter of Britain, in all sorts of ways, and they removed that from the book completely.

Do you think it’s hard for an American film company to deal with that subject matter?

They wanted to set it in New England, so they said “Suppose he were an American boy brought back to roots of his family?” I thought that might conceivably work, but what they did with it certainly didn’t work.

A lot of British classic books have been changed in similar ways when made into Hollywood films.

You have explained that myth was an important part of your classical education but did your interest go back before Oxford? Were you reading the old stories as a child?

Yes both by accident or by design. Mythology fascinated me. My mother was a teacher, and I think either read to us or made sure that we read. I was ten when World War Two ended, and I was reading everything I could get my hands on. We weren’t within reach of a public library so I read what was in the house and that happened to be folktales, myths and fairy stories. I grew up haunted by this sort of stuff.

Of course the sequence is also a good adventure story, and derives a lot from classic adventures too.

Yes. The big adventure in my childhood was Arthur Ransome, which is not fantasy, but the parent’s are conveniently out of the way all through it.

Writing children’s books is just one aspect of your writing life. You’ve been a journalist; you’ve written screenplays, you’ve been a playwright as well.

Yes, jack of all trades.

Didn’t you once work with Ian Fleming?

When I came down from Oxford, I went to see every journalist I’d ever met through the Press Club at the University. The News Editor of the Sunday Express gave me a six week trial as a Saturday Reporter. I was let go at the end of the six weeks because I’d been sent to get a story about Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe who were holed up somewhere outside London. I went back to the office and said, “Well, you know, there are policemen at both gates, and there’s a wall with broken glass on top,” And they said to me, “You should have climbed over the wall.”I thought, “That’s not my kind of journalism.”

After that the Sunday Times News Editor, gave me a trial and he said, “All I can offer you is a flower show; it’s the National Rose Show, the Horticultural Halls in Westminster.” He said, “You can write a 1,000 word colour story.” SoI went to this Rose Show, and there were all these old ladies and gentlemen wandering about, talking to the rose growers. Just as I was leaving, I heard this little old lady say to a rose grower, “How far apart should I keep my Passions?” He said, “18 inches is a safe distance Madam.” And that was my lead!

At the next Tuesday editorial meeting my piece was discussed. The News Editor liked it and wanted to take me one but there was a Cambridge boy he wanted as well and the budget wouldn’t stretch to both. Ian Fleming was Foreign Manager and writing a column called Atticus and he offered to pay half the salary so that we could both be taken on. So I was working half of the time for Ian and half for the News Department. Ian was a tall, sophisticated presence, chain smoking, driving a black Ford Thunderbird, a very striking figure in 1960s London.

Was journalism a good training ground for novel writing?

I think it was, because you have to be succinct and think clearly. It gives you the ability to write anywhere, under any circumstances and meet a deadline. However, you need to break free from journalism before it drags you down. Most of the reporters I knew had seen too much, and were disenchanted with the world.

Perhaps the cynicism is inevitable if you spend too long as a reporter.

How did the screenplay writing come about?

It was because I had met two actors: Hume Cronyn, who was Canadian, but living in America and Jessica Tandy, who was English, but was living in America. I met them on holiday while I was writing The Grey King. We had a little house in the British Virgin Islands and we met Hume one day when Jessica had a sunburn and was resting inher room. When he went back he said “I’ve met this American who I’m going to go fishing with, and his wife is a countrywoman of yours. She writes children’s books, and I think she wrote a book about J B Priestly.” And Jessie said, “Not Susan Cooper? She wrote that book I’ve been trying to get you to read for the last six month, which was The Dark is Rising.

We became good friends, and Hume and I wrote a play together called Foxfire for the two of them. The genesis was a bunch of magazines called Foxfire, which had been started by an English teacher down in Appalachia, whose kids didn’t want to listen to Julius Caesar. He gave them tape recorders, and sent them out into the mountains to interview their grandparents. So they came back with all these old stories. From these old stories, we invented two old people and wrote a play with songs. The son of the couple in the play is a singer.

At that time Hume was making a film called Rollover with Jane Fonda and Kris Kristofferson. Kris was a country singer as well as an actor, so we gave him our script to see if he thought it was realistic. Jane Fonda noticed him reading it and pinched it one day so when I visited the set she asked me if I had read a book called The Doll Maker by Harriette Arnouw. By chance my publisher had been trying to get me to read that very book.

So I read it. A wonderful book, with this very strong woman as the central figure. Jane had the rights to this book for ten years, because she really wanted to play that woman. She had two scripts written and didn’t like either of them. So she asked Hume and me to write it. We did and she liked it. It was produced for ABC Television. We all got nominated for Emmys and Jane got one so everybody thought we were screenwriters! That’s where it started.

Around that time, my marriage broke up, and I had joint custody of my children, so I needed more money than you can earn by writing children’s books – for practical reasons the screenwriting became important. Mostly I adapted other people’s books, which is ironic.

So you learned screenwriting on the job…

Exactly, like all my writing. I’ve never been taught what the Americans call creative writing and in any case I don’t think it can be taught. You can teach grammar and you can soak people in good writing, which is what a degree in English is about, but you can’t teach creativity.

A screenplay is very spare writing, so how did the novelist in you cope with that?

I think screenplay writing is not too difficult for a novelist. The narrative structure of the film is like the narrative structure of a novel. Yes, you do have to think differently, and you have to pare the writing down to give the Director a chance to do things with scenes and themes and characters but essentially the different forms have a lot in common.

Playwriting is more challenging. You have to have a sense of theatre and what will work on stage, which is why so many good playwrights start as actors. I’m not a natural playwright. I wish I were.

Yes, with a play what isn’t there in the writing is really important. I’m thinking of Pinter here…

I imagine that writing a screenplay that is an adaptation of a book must in some ways be more challenging than writing an original screenplay.

I think you really need to be in love with the book. I always turned down books that I didn’t feel comfortable with. I believe John Hodge has said in an interview that he turned down The Dark is Rising earlier. Some other producer – one of the two that I gave it to presumably, had asked him to do it, and he didn’t find it attractive, and I think his instinct then was right.

I suppose one of the differences is that you’re very much on your own as a novelist but writing a screenplay is collaborative. Do you like working with other people on a creative endeavour?

Yes, I like to alternate. When you are writing a novel you are on your own for such a long time that you begin to yearn for the family feel of working on a film. On the other hand, you have to be prepared to bleed a great deal if you’re writing a script, because so many people have a say as to how it should be changed. Having done some bleeding, you want to go back and write a book.

Stage plays evolve in the rehearsal process; the final script is never exactly the same as the rehearsal script...

You learn a lot from the actors. It doesn’t change story very often but certainly changes dialogue and incident. When you find things that just don’t work, you learn a great deal. Twice I’ve been on a television film set all the way through the shoot, and that’s interesting too, because an actor might have trouble saying something, or you’ll hear it and know that it’s not right, and you can change it right in front of the camera.

I’m really interested in dialogue, because I think that, mistakenly children are taught at school to write playscripts as though they are dialogue but that’s a small part of what a play is.

That’s right. That’s why Pinter is so wonderful as you said earlier

… yes and Beckett…

Emotion has to carry through in the gaps between the dialogue.

Has the skill you’ve acquired from playwriting had any impact on the way you write dialogue in novels?

No, I don’t think so. You’re wearing a different hat when you’re doing the two things. Literary dialogue doesn’t translate straight to stage or film, and the same thing is probably true in reverse.

It is fascinating.

It is, isn’t it? You can’t just take direct speech and write a play from it. You can’t just record speech and put it into a novel.

I suppose the one playwright read for pleasure is Shakespeare, though personally I think his plays are best taught as plays.

Well yes, exactly. I got into trouble with Oxford because I quoted the Prefaces of Harley Granville Barker, in a long essay on Shakespeare, and my tutor said, “Well this man is not a scholar that you’re quoting. He’s from the theatre.” Theatre – Shakespeare was a working dramatist. He was writing for the stage. Though, of course the words are so beautiful that we do read it as poetry rather than – but you can’t compare anybody else to Shakespeare.

When I was at University I took a few master classes with Ian McKellen and Prunella Scales and through hearing them read Shakespeare, I learnt about the nuances of meaning that come from hearing Shakespeare read aloud by skilled actors. Sometimes a passage could be read to convey the opposite to how I had interpreted it. I think you discover Shakespeare by reading him aloud.

It’s true. That’s the acid test of a great playwright, isn’t it? Have you read a book I wrote called The King of Shadows?

Yes.

‘The chance to met Shakespeare through writing it was just magical.

Your writing is very diverse. It simply isn’t possible to pigeon-hole Susan Cooper.

I’ve done exactly what – J B Priestly advised against. He once told me “Don’t be like me. I have been a jack of all trades. I’ve done almost everything, because I got bored with doing the same thing over and over and over again.” And he had. He wrote plays and he wrote novels and he wrote essays. “Better,” he said, “to be the same brown cow in the same green field, because then they can say, “This man is the best writer about brown cows and green fields that ever existed.””

I got to know Priestley when I wrote an article about the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. He wrote me this little note afterwards, saying, “That was a good piece. If I can ever help you in any way, let me know.” And about a year later I sent him my first novel with a little note saying, “Well you did say, if I needed any advice…” He invited me to tea, and we just liked each other.

After I went to America, he used to write to me. He once told me, “Don’t despair. You will find you write better about a place when you are away from it.”

What’s coming next? Are you writing a new children’s book?

Something is bubbling away in my head. I’ve written two historical fantasies in the last five years and I don’t want to do that again. I want to go back to the kind of fantasy I was writing with The Dark is Rising and Seaward.

And will it be set in America or England?

I’ve never even written about the one part of America that has always fascinated me - the Navajo lands and the Hopi lands in New Mexico and Arizona, because I don’t feel I’ve got the right.

I live on a piece of land on an island in a salt marsh where there are just three houses. We’re surrounded by water at high tide. I look out at the marsh and I think, “People have been living here, and in one way or another, living off this countryside, for just as many thousands of years as in Britain, but the race that I came from just destroyed it, in order to take it over.” But this place where I’m living now might well be the inspiration for a new book, if I can find the right story and the right way of telling it.

No comments:

Post a Comment